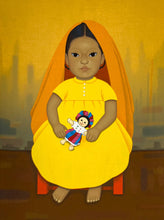

Unframed silkscreen prints in colors on paper, signed lower right G. Montoya (Gustavo Montoya, Mexican, 1905-2003), from the "Ninos Mexicanos" series, published by Bernard Lewin Galleries, each signed lower right, from an edition of 250, with a blind stamp.

Each sheet measures 27 x 21 inches 67.5 x 52.5cm.) and they were done in 1985.

Printed by Multiarte Editions, Enrique Cattaneo Workshop.

The Mexican Children series, Gustavo Montoya contributed to the aesthetics of the Mexicanity of the twentieth century. It puts us in front of the nuances of traditional Mexico: the face of the children of Taz Morena and almond eyes; The watermelon that color the markets, the dish of Olinalá, the hand painted chair, the sound of the jarana and the earth that step on the bare feet.

To get an idea of the retail value of these work:

https://gustavomontoyaserigraphs.com

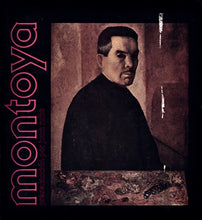

Gustavo Montaya (Mexico City, July 9, 1905 - July 12, 2003) was an artist associated with the Mexican School of Painting. Born to a father who worked for the government under Porfirio Diaz, Montoya's family was forced to go into hiding after its overthrow at the beginning of the Mexican Revolution, often moving from home to home at night and adopting different disguises to evade the Zapatistas. At the age of 4, Montoya had already begun to present phobias and a deep depression that were only exacerbated by the Revolution's effect on his life, a violent father, and a neurotic and strictly religious mother.

At the age of fifteen Montoya entered the Academy of San Carlos where he studied under German Gedovius and Roberto Montegro. Although he had to overcome the objections of his father to enter the school, Montoya ultimately felt that the school taught him the craft of painting and not the spirit, and for this reason he considered himself a largely self-taught artist. He began his artistic career making paintings for posters with West Coast Theaters Co in Hollywood, CA after marrying his first wife Luz Saavedra. Their relationship was not to last and Montoya eventually returned to Mexico City to marry Cordelia Urueta, convincing her to rent studio space with a number of other artists.

Urueta took a position at the Mexican Embassy in Paris which, when Montoya received a grant from the Mexican government to study avant garde art in Switzerland, Italy, and England, allowed him to further refine his style in addition to experimenting with techniques such as painting with his non-dominant left hand. Making a stop to exhibit his work in New York City, the artist returned to Mexico in 1942, where he joined his contemporaries in the Mexican movement emphasizing neo-realism and muralistic techniques.

Montoya is most well-known for his colorful portraits of children in Mexico City, often accompanied by simple backdrops including apartment rooms or mountainous scenery. Focusing on the poor and working class, his portraits and street scenes portrayed people in the traditional style of the region, which has since earned him the esteem of collectors with appreciation for the Mexican School of Painting. In addition to portraits and scenes of the street and market, Montoya painted still lifes of Mexican food, often featuring the fruits and breads of the area. He was a founding member of the Salon de la Plastica Mexicana (The Hall of Mexican Fine Art) and Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios, a group of revolutionary writers and artists against government censorship and violations of universal peace in the name of Nationalism such as Hitler and Mussolini's ambitions and actions by the leaders Spanish Civil War.

Referred to as a "Great Silent One" in a posthumous anthology of work issued by the Museo Mural Diego Rivera in 1997, during his life Montoya exhibited at the Durand Gallery, the Galeria de Plastica Mexicana of Ines Amor, the first Bienal Mexicana at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the second Bienal Panamericana, Beverly Hills Collectors Gallery in Los Angeles, the Museum of Modern Art in San Antonio, Texas, Galeria Arte Nucleo, and Galerie Marstelle. He died on July 12, 2003, survived by his third wife Trina Hungria.

Mexico has the oldest printmaking tradition in Latin America. The first presses were established there in the 16th mainly to print devotional images for religious institutions. Because of their ephemeral nature, few of these early impressions survive. A rare early exception is a 1756 thesis proclamation printed on silk presented by a candidate for a degree in medicine. With the introduction of lithography to Mexico in the nineteenth century, printmaking and publishing greatly expanded, and artists became recognized for the character of their work. José Guadalupe Posada (1851–1913) is often regarded as the father of Mexican printmaking. His best-known prints are of skeletons (calaveras) published on brightly colored paper as broadsides that address topical issues and current events, love and romance, stories, popular songs, and other themes. Posada demonstrated how effective prints were for creating a visual language that everyone could understand and enjoy. In the early twentieth century, their example had a profound impact on artists who, in response to the turbulent political climate and social unrest, were similarly eager to reach broad audiences.

The best-known artists in Mexico from the early decades of the twentieth century are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949), and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974)—“Los tres grandes” (The Three Greats). They were all committed to politics but expressed their views through their art in very different ways. Of the three, Rivera—who returned to Mexico from Europe at the invitation of the government in 1921 to work on a mural project—rose to greatest prominence. Rivera’s 1932 lithograph Emiliano Zapata and His Horse, based on a detail from one of his murals at the Palace of Cortés Cuernavaca to the south of Mexico City, has become an iconic twentieth-century print. Zapata was a landowner-turned-revolutionary who formed and led the Liberation Army of the South. He embodied the aims of agrarian struggle that aspired to improve conditions for those who worked on the land. Zapata was assassinated in April 1919. Rivera’s print conflates different moments of oppression with optimistic emancipation. It was commissioned and published by the Weyhe Gallery in New York for sale to American collectors. Orozco and Siqueiros also made prints for the U.S. market, a number of which are devoid of political content.

The establishment of the print collective known as the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Workshop of Popular Graphic Art, TGP) in Mexico City in 1937 best expresses the symbiosis between prints and politics that had developed in Mexico. Its founders, Leopoldo Méndez (1902–1969), Luis Arenal (1908/9–1985) and Pablo (Paul) O’Higgins (1904–1983), were committed communists who abandoned mural painting to concentrate on printmaking, demonstrating how important prints had become as a vehicle for artistic, social, and political expression. Some of its members had belonged to the League of Writers and Revolutionary Artists (LEAR), which had been launched in 1934. The TGP has a fascinating history steeped in astonishing artistic production and political intrigue. The Bolshevik revolutionary and Marxist theorist Leon Trotsky arrived in Mexico in 1937, much to the horror of the communists represented by Siqueiros, who regarded him as a pro-fascist provocateur. Rivera was a supporter of Trotsky and established a Mexican branch of the Fourth International, a socialist organization that had its own journal, Clave, and ran articles attacking the USSR and the Mexican Communist Party. Siqueiros, then a guest member of the TGP, with fellow printmakers Antonio Pujol (1913–1995) and Luis Arenal, led an attempt to assassinate Trotsky in May 1940. The TGP workshop was their rendezvous point. After the failed attempt, Pujol ended up in prison and Siqueiros fled the country. Their action caused terrible ruptures in the TGP, with some remaining committed to the communist cause and others pressing for a more moderate line.

By 1947, the year that the Society of Mexican Printmakers was founded, printmaking had broadened its horizons far beyond its proletarian roots. In fact, printmaking was now considered to be the most intimate of media. Post World War II artist felt a need to reassert private values in opposition to highly politicized work. They opened the way to more subjective investigations of personal identity and myth.

Jose Luis Cuevas, Rufino Tamayo, and Francisco Toledo are fine examples of the new sensibility. These later artists have kept alive Mexico’s reputation for excellence in the graphic arts. A common Mexican trait on either side of the U.S.–Mexico border is the passionate interest in Mexicanidad (Mexicanness) and what comprises Mexican identity. Perhaps this obsession to understand the concept of Mexicanidad comes from nearly five centuries of mestizaje – the interracial and cultural mixing that first occurred in Mesoamerica among Native Indigenous groups, European Spanish and enslaved Africans during the 1520s. By the 18th century, Mexican identity had developed. Mestizaje was the process that constructed it. The museum’s permanent collection showcases the dynamic and distinct Mexican stories in North America, and sheds light on why Mexican identity cannot be regarded as singular; its vast diversity defies any notion of one linear history. -

Nuestras Historias destaca la colección permanente del museo, la cual expone las historias dinámicas y diversas de la identidad mexicana en Norteamérica. La exhibición muestra la identidad cultural como algo que evoluciona continuamente a través del tiempo, de regiones y de comunidades, en vez de señalarla como una entidad estática e inmutable, exhibiendo para esto, artefactos mesoamericanos y coloniales, arte moderno mexicano, arte popular, y arte contemporáneo de los dos lados de la frontera EE.UU-México. La gran diversidad de identidades mexicanas mostradas en estas obras desafía la noción de una sola historia lineal e identidad única.