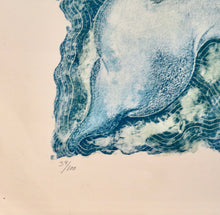

A large print measuring 22" x 31" (56cm. x 78cm.), in very good condition. Signed and numbered from an edition of 100. Done by Taller Lithografias Leo Acosta, Mexico City, in 1986. Marked down to celebrate our 25th anniversary.

A simple black bow above the door of La Mano Magica heralded the bad news. On March 9, 2014, Arnulfo Mendoza, known for his unmatched skill as a rug weaver, died at the age of 59.

To say that Arnulfo Mendoza was just a rug weaver is to say that Caruso was just a singer, Stradivarius just a woodworker, Michael Jordan just a basketball player and Bill Gates just some computer guy.

The reality is that Arnulfo Mendoza was one of the grand masters of Oaxacan art.

Unfortunately, too few people came to appreciate the great designs he created out of nondescript balls of yarn. For far too many people, the tapete, as it is known here in Oaxaca, was simply too utilitarian. After all how could someone call something art if its chief function was as a floor covering?

I remember the first time I walked into his store/gallery and realized that not only was I enthralled by Arnulfo’s work, but that he was sitting in the back of the store enjoying a cold beer. Humble and unpretentious, I sensed back then, not knowing who he was, that I was somewhere special, near a man who literally worked magic with his weavings. From that day on, every time I visited Oaxaca, I made the pilgrimage to his shop to see his creations.

I bring people every year to Oaxaca to experience part of the culture of this great area. One year one of the people who was traveling with me pulled me aside to ask a question. He had been walking along the Alcade in Oaxaca and said he had gone into a store called the “La Mano Magica, or something like that.” He wanted to know if I had any idea how much a rug from there might cost.

Clearly, he could sense the difference between what he saw there and what is typically available on the street corners and in the markets across Oaxaca. What he was looking at was art. Delicate and at the same time, robust. Intricate on such as scale that when seen whole, Mendoza’s creations were mind blowing.

Standing in his gallery, looking at his creations, you just knew that Mendoza, and his work, were special. You got the same feeling admiring his work as you would in one of the worlds great art museums. Indeed, many of the stunning creations he wove over the years hung next to some of the greatest art we have ever seen.

As well it should.

El Maestro Arnulfo Mendoza will be missed, but not forgotten. Through his art, his legacy will live on, hopefully challenging the young weavers growing up in his hometown, Teotitlan del Valle, to further greatness.

Descansa en Paz Sr. Arnulfo Mendoza. You were and will continue to be, the standard of greatness to which all future generations of weavers will be measured.

By Oaxacadave.

Arnulfo Mendoza Ruiz (August 17, 1954 – March 7, 2014) was an artist and weaver, who exhibited his work both in Mexico and abroad. Born in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, a well-known center for traditional Zapotec weaving, he became one of its best-known artisans, recognized as a “grandmaster” by the Fundación Cultural Bancomer. As director of La Mano Mágica gallery and with his former wife Mary Jane Gagnier, he also worked to promote Oaxacan arts and handicrafts.

Mendoza was born in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, a Zapotec community near the state capital that is well known for its weaving of rugs. The residents have been successful enough in this endeavor that unlike many other communities in the region, few people emigrate from here.

At age nine, he began his training in form, color and materials at his family’s workshop, learning traditional Zapotec weaving. He went on to study at the school of fine arts at the Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca (UABJO) from 1972 to 1974.

Mendoza later married Canadian Mary Jane Gagnier, who had come to Teotitlán as a backpacker and fell in love with the area, as well as with him. They worked together to promote his work and that of other artisans in the central valleys of Oaxaca, by opening a gallery, La Mano Magica, and writing. The couple divorced but Mary Jane stayed in Oaxaca to continue this work. The couple has one son, Gabriel Mendoza Gagnier.

In 2014, Mendoza died unexpectedly of a heart attack at age 59. There was a wake in the city of Oaxaca as well as in his hometown, where he was buried.

Mendoza was one of Teotitlán’s most famous weavers, whose works sold for up to thousands of dollars.He dyed his own silk and wool yarn and was particularly partial to the reds produced by the cochineal insect and sometimes used silver and gold thread. He had over fifty individual and collective exhibitions of his work, including in museums in New York, Madrid, Dallas, Paris, Los Angeles and Berlin. In 2003 his work was featured at the Weaving a Cultural Testimony exhibit at the Mexican Art Museum in Chicago.

His work can be found in many private, and permanent collections of the Mexican Art Museum in Chicago, Tama Life 21 in Tokyo, Fundación Cultural Banamex, Waterloo Center for the Arts in Iowa and published in Cuento Mayas, Native Tradition (1982), Textiles de Oaxaca, Artes de México No.35 (1997) and Oaxaca Celebration (2005).

In 1980 he traveled to Paris to paint for a year. From 1987 to 2010 he founded and directed the Arnulfo Mendoza Workshop, producing tapestries with traditional and contemporary designs. In 1993 he participated in an International Art Project in Japan, with two of his works acquired by the largest public art collection in Tokyo. From 2009 to 2010 he was the co-director of the La Mano Mágica Gallery, one of the most recognized in Oaxaca. In 1996, the Fundación Cultural Banamex named him of one their “grandmasters” of Mexican folk art (Grandes Maestros del Arte Popular Mexicano). In 2001 he was awarded the Chimalli de Oro by the El Imparcial newspaper.

Mexico has the oldest printmaking tradition in Latin America. The first presses were established there in the 16th mainly to print devotional images for religious institutions. Because of their ephemeral nature, few of these early impressions survive. A rare early exception is a 1756 thesis proclamation printed on silk presented by a candidate for a degree in medicine. With the introduction of lithography to Mexico in the nineteenth century, printmaking and publishing greatly expanded, and artists became recognized for the character of their work. José Guadalupe Posada (1851–1913) is often regarded as the father of Mexican printmaking. His best-known prints are of skeletons (calaveras) published on brightly colored paper as broadsides that address topical issues and current events, love and romance, stories, popular songs, and other themes. Posada demonstrated how effective prints were for creating a visual language that everyone could understand and enjoy. In the early twentieth century, their example had a profound impact on artists who, in response to the turbulent political climate and social unrest, were similarly eager to reach broad audiences.

The best-known artists in Mexico from the early decades of the twentieth century are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949), and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974)—“Los tres grandes” (The Three Greats). They were all committed to politics but expressed their views through their art in very different ways. Of the three, Rivera—who returned to Mexico from Europe at the invitation of the government in 1921 to work on a mural project—rose to greatest prominence. Rivera’s 1932 lithograph Emiliano Zapata and His Horse, based on a detail from one of his murals at the Palace of Cortés Cuernavaca to the south of Mexico City, has become an iconic twentieth-century print. Zapata was a landowner-turned-revolutionary who formed and led the Liberation Army of the South. He embodied the aims of agrarian struggle that aspired to improve conditions for those who worked on the land. Zapata was assassinated in April 1919. Rivera’s print conflates different moments of oppression with optimistic emancipation. It was commissioned and published by the Weyhe Gallery in New York for sale to American collectors. Orozco and Siqueiros also made prints for the U.S. market, a number of which are devoid of political content.

The establishment of the print collective known as the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Workshop of Popular Graphic Art, TGP) in Mexico City in 1937 best expresses the symbiosis between prints and politics that had developed in Mexico. Its founders, Leopoldo Méndez (1902–1969), Luis Arenal (1908/9–1985) and Pablo (Paul) O’Higgins (1904–1983), were committed communists who abandoned mural painting to concentrate on printmaking, demonstrating how important prints had become as a vehicle for artistic, social, and political expression. Some of its members had belonged to the League of Writers and Revolutionary Artists (LEAR), which had been launched in 1934. The TGP has a fascinating history steeped in astonishing artistic production and political intrigue. The Bolshevik revolutionary and Marxist theorist Leon Trotsky arrived in Mexico in 1937, much to the horror of the communists represented by Siqueiros, who regarded him as a pro-fascist provocateur. Rivera was a supporter of Trotsky and established a Mexican branch of the Fourth International, a socialist organization that had its own journal, Clave, and ran articles attacking the USSR and the Mexican Communist Party. Siqueiros, then a guest member of the TGP, with fellow printmakers Antonio Pujol (1913–1995) and Luis Arenal, led an attempt to assassinate Trotsky in May 1940. The TGP workshop was their rendezvous point. After the failed attempt, Pujol ended up in prison and Siqueiros fled the country. Their action caused terrible ruptures in the TGP, with some remaining committed to the communist cause and others pressing for a more moderate line.

By 1947, the year that the Society of Mexican Printmakers was founded, printmaking had broadened its horizons far beyond its proletarian roots. In fact, printmaking was now considered to be the most intimate of media. Post World War II artist felt a need to reassert private values in opposition to highly politicized work. They opened the way to more subjective investigations of personal identity and myth.

Jose Luis Cuevas, Rufino Tamayo, and Francisco Toledo are fine examples of the new sensibility. These later artists have kept alive Mexico’s reputation for excellence in the graphic arts. A common Mexican trait on either side of the U.S.–Mexico border is the passionate interest in Mexicanidad (Mexicanness) and what comprises Mexican identity. Perhaps this obsession to understand the concept of Mexicanidad comes from nearly five centuries of mestizaje – the interracial and cultural mixing that first occurred in Mesoamerica among Native Indigenous groups, European Spanish and enslaved Africans during the 1520s. By the 18th century, Mexican identity had developed. Mestizaje was the process that constructed it. The museum’s permanent collection showcases the dynamic and distinct Mexican stories in North America, and sheds light on why Mexican identity cannot be regarded as singular; its vast diversity defies any notion of one linear history. -

Nuestras Historias destaca la colección permanente del museo, la cual expone las historias dinámicas y diversas de la identidad mexicana en Norteamérica. La exhibición muestra la identidad cultural como algo que evoluciona continuamente a través del tiempo, de regiones y de comunidades, en vez de señalarla como una entidad estática e inmutable, exhibiendo para esto, artefactos mesoamericanos y coloniales, arte moderno mexicano, arte popular, y arte contemporáneo de los dos lados de la frontera EE.UU-México. La gran diversidad de identidades mexicanas mostradas en estas obras desafía la noción de una sola historia lineal e identidad única.